Some of the earliest British photographers were traditional academic painters.

In England, Henry Colin, a successful Miniaturist, bought Fox Talbot’s first licence to take Calotypes professionally.

In Scotland, no such licence was needed, and in 1843, the landscape painter David Octavius Hill formed a partnership with Robert Adamson which created the first collection of masterpieces in the history of photography.

Robert Adamson came from the Scottish coastal town of St Andrews, where he was apprenticed to a millwright. He soon however proved too sickly for such work, his illness was not known, but given how rife it was at the time, it was probably tuberculosis.

D.O.Hill, 20 years his senior, was born into a large family in Perth. He became an art student in Edinburgh, where he learned lithography.

Hill witnessed the mass resignation of ministers from the Church of Scotland, and their subsequent establishment of the new ‘Free’ Church. This was an event he determined to celebrate.

Hill was primarily a landscape painter and his major problem was recording the faces of nearly 500 participants before they left Edinburgh. Sir David Brewster of St Andrews University knew that a colleague of his, John Adamson and his brother, Robert, had taken some Calotypes.

He showed these to him and suggested that they collaborate. Robert Adamson had gone to Edinburgh on the ninth of May, 1843, only days before the disruption of the Church of Scotland. Within weeks he and Hill were taking photographic studies for the proposed painting, which Hill took 23 years to complete.

Hill and Adamson’s Calotypes were first merely reference material for the painting, but they rose above Hill’s dull academicism, partly because they were so difficult to make.

The Calotype by its very nature was more suited to subtle portraiture than the sharply detailed metal Daguerreotype. It also lent itself to beautiful gradations of light and shade, which needed an artist’s eye to control and exploit them.

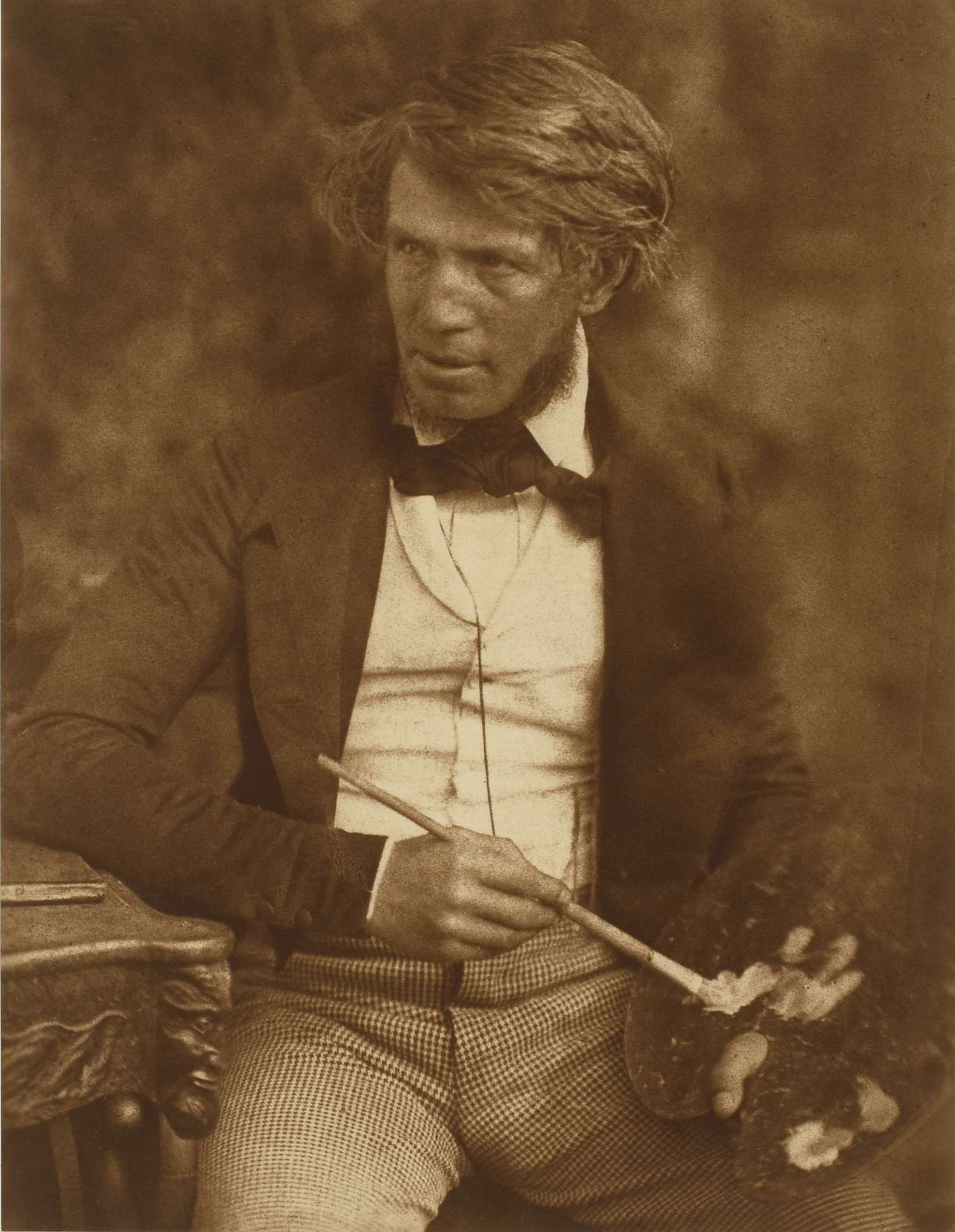

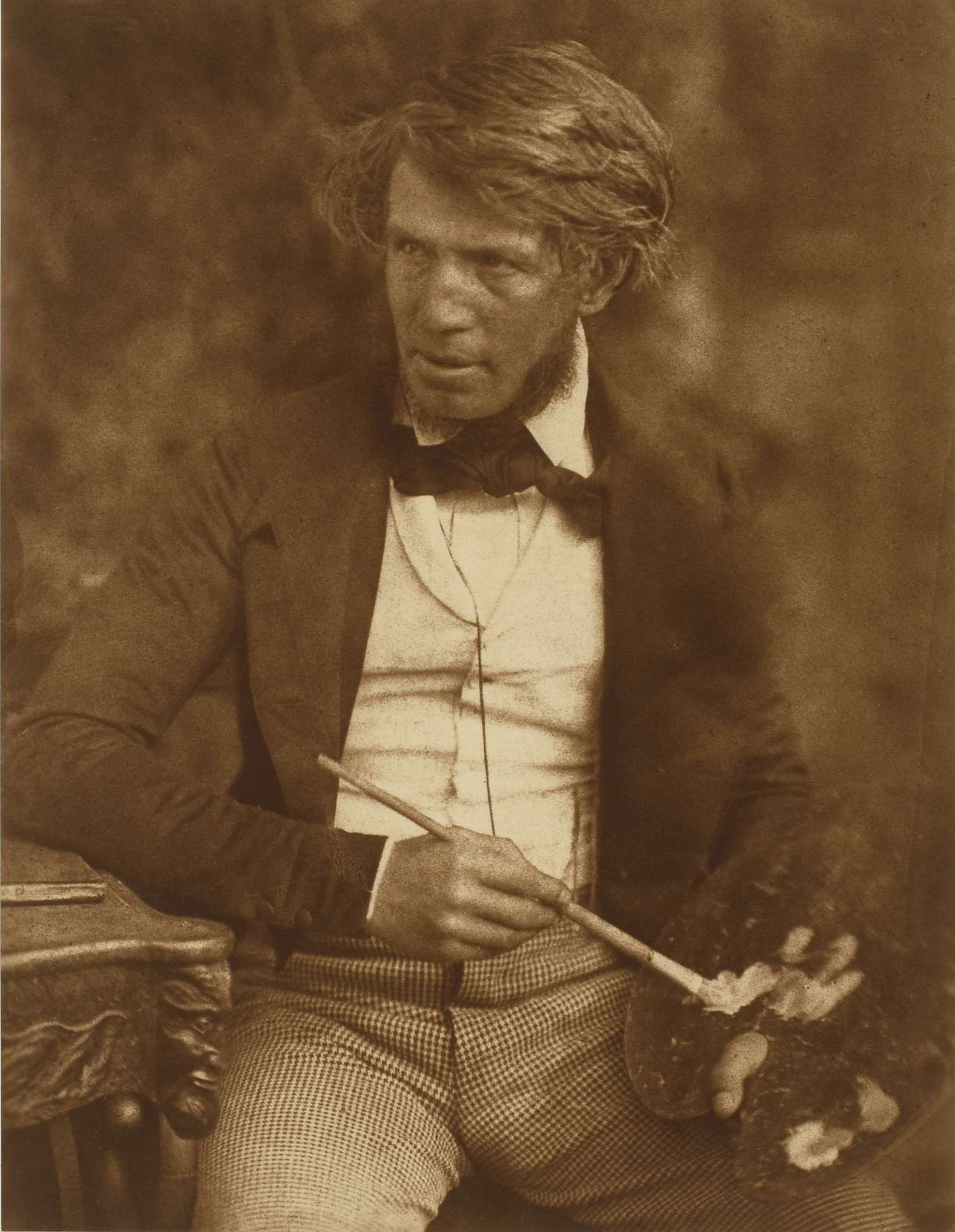

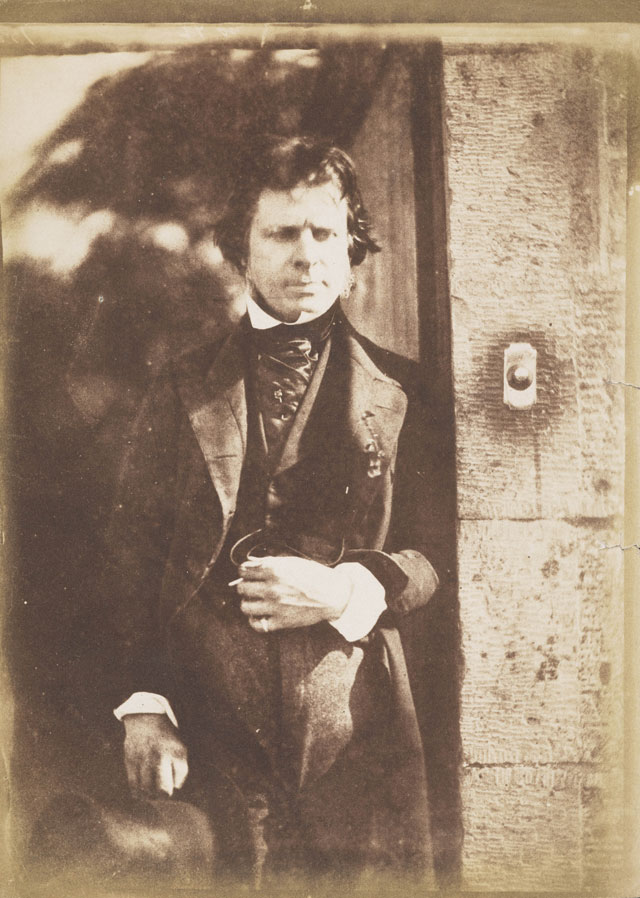

When Hill and Adamsons work was first exhibited at the Royal Scottish Academy of Arts (of which Hill was secretary) it was described as ‘executed by R.Adamson under the artistic direction of D.O.Hill’. This reflected the fact that Hill arranged the sitter’s costumes and background while Adamson dealt with the equipment and processing.

By this time Hill had moved into Adamson’s home. There are photographs later bore the legend ‘published by D.O.Hill and Robert Adamson at their Calotype Studio, Carlton Stairs’. But it was not really a studio, taking Calotypes needed so much light that they had to be done outdoors. As a close look at several of the pictures shows clearly, even in bright sunshine and with a mirror reflecting light onto the shadows, they usually had to expose their negatives for some minutes, too long for any setup to keep still at all, easily.

Fortunately, Hill devised poses that placed sitters leaning on their hands, on the arm of a chair, on a heavy book, on a stick, or more fashionably an umbrella. These supports helped the sitters to keep still, though the strain of doing so meant that some of the portraits were failures.

Hill and Adamson also used the headrest or tripod, of the type later to become standard in commercial portrait studios. Of course, the sitter was usually posed so that this could not be seen in the finished picture, but sometimes it was not properly hidden. Here again Hills training was invaluable and he carefully over painted the tripod. Telltale signs of it remained However, in a number of portraits.

He also used other subtler forms of retouching as Calotypes were made on ordinary writing paper impregnated with chemicals, the watermarks sometimes had to be disguised. Unclear detail was clarified, lettering and other information added. But Hill never altered faces; his retouching is quite different from the wholesale prettifying, which was to become part of the portrait photographers stock in trade.

Most of Hill and Adamson’s pictures were taken at Rock House for technical reasons. Adamson, who became perhaps more expert in the Calotype process than anyone else, obtained his best results when he used the paper immediately after he had sensitised it. This is possibly why the partnership took far less landscapes than Hills earlier artistic interests might suggest.

A number of Calotypes were made in the picturesque Greyfriars Cemetery, as well as Edinburgh Castle and the fishing village of New Haven where they photographed the houses and seashore, and made many poignant studies of the sailors and fish wives.

But most of their subjects came to them, a missionary with red Indian ancestry and costume, a Highland Chief, an Irish harpist. Hill himself was often in front of the camera. Happy to dress up or take part in a tableau. The shy and retiring Adamson appears more rarely. Hills’ ceaseless and extroverted activity must have been a strain on his limited strength. In December, 1847, he went to St Andrews for a family Christmas, and a rest. Early in the new year he died aged only 27.

Hill did not want to give up on his new interest, he tried to persuade John Adamson to take over his brother’s work, but failed. His own four and a half years involvement with photography taught him little of its vital chemistry, and so, reluctantly, he was forced to abandon it. It was a very remarkable sort of chemistry that fused together two such dissimilar men in a brief, highly intensive burst of creativity. Together they became the first ‘Old Masters’ of photography.