What is aperture?

Aperture literally means a hole, an opening or a gap. A window can be an aperture, a vent or passage can be an aperture. Because we love the English language and all its subtleties, we must wrap context around a word in order to better understand it.

In my experience of teaching, Aperture is one of the hardest things for new photographers to get their heads around. Whilst it is complex, don’t worry, you don’t have to understand all of the physics and engineering, you only really need to know how it affects your exposure and how it affects what is in focus and what is out of focus.

Aperture; what are you, tell me your secrets!

aperture

noun

1. an opening, hole, or gap.

“the bell ropes passed through apertures in the ceiling”

Literally, aperture means a hole.

When you take a picture, you don’t want it to be too dark or too bright, right?

The control of that is called exposure.

Controlling the exposure means you control how bright/dark the image is.

Aperture is one of the three components of exposure. The other two being shutter speed and ISO.

Have you ever wanted to know how to blur the background in a photograph?

The thing that controls that, is the aperture.

It’s not an effect or an Instagram or Photoshop filter, it’s a mechanical movement within the lens. Let’s get into it.

Brief Explanation of Aperture

In the context of photography aperture is: “a space through which light passes in an optical or photographic instrument, especially the variable opening by which light enters a camera”

Basically, a hole that opens and closes, controlling the rate at which light can get in.

If you open the back of a film and press the shutter release, or if you remove the lens from the body and look through it, you can see the aperture.

The aperture controls the amount of light that can pass through it and consequently, how much light can reach the film or sensor.

Aperture size, and therefore brightness, is controlled by the iris diaphragm. The iris is made up of a number of thin, interleaving blades which rotate to make the aperture larger or smaller.

Making it smaller reduces the amount of light that can pass through, making it bigger increases the amount of light that can pass through.

Takeaway: what is the aperture? – it’s the hole in the lens that lets in light

What the hell is an F number?

The F number system, the brightness of the image on the film depends on the combination of the aperture size and the focal length of a lens.

So a large aperture and long focal length can transmit the same brightness of light, as a small aperture, and a short focal length.

The scale photographers use to relate focal length and aperture size is called the F number system.

F stands for the mathematical term Factor, and it is calculated by measuring the diameter of the aperture and dividing it into the focal length.

An aperture of 25 millimetres on a 100 millimetre lens represents f4, but the same diameter aperture on a 50 millimetre lens will represent f2.

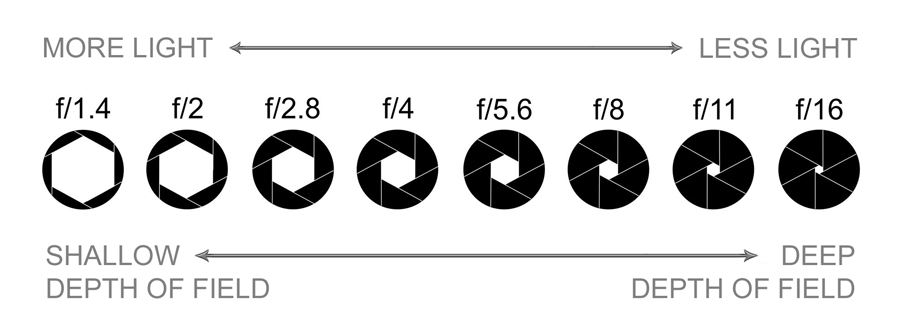

The smaller the F number, the larger the aperture, and therefore, the more light reaches the film.

The F numbers for any lens are calibrated by the maker, on the basis that an aperture of F8 will always transmit the same brightness of light, whatever the focal length.

The brightness of the image on the film depends on the combination of the aperture size and the focal length of the lens. A large aperture and a long focal length can transmit the same brightness of light as a small aperture and a short focal length.

This may seem like a very complicated way of measuring the power of a lens to transmit light. However, it has certain advantages.

Telephoto lenses form a magnified view of the subject, compared with wide-angle or standard lenses. So the light from a given area of the subject is spread over a larger area of film with a telephoto lens.

This means there is less light for any given aperture diameter.

The f-stop system gets around this problem because it is independent of focal length. An f-number is a ratio, not an actual measurement, so an aperture of f8 on a 50mm lens admits exactly the same amount of light as an aperture of f8 on a 400mm lens but the physical size of the hole itself has changed.

This is important when changing lenses. A photographer who is switching from one lens to another can maintain the same f-number on both lenses. If the aperture was measured in millimetres, instead of as a numeric ratio, lenses of different focal lengths would need to be set differently.

Why then the curious progression of numbers? Again the choice is quite logical. Each setting of the aperture ring lets through twice as much light as the one before, so with the lens set at f/4, the image on film is twice as bright as at f5.6, and half as bright as f2.8.

This doubling/halving sequence may be familiar – shutter speeds increase and decrease in a similar manner.

Note, though, that large f-numbers let through little light, and small f-numbers, such as f2, admit very much more light.

Takeaway:

– Going up in F number? You’re letting in less light. Going down in F number? You’re letting in more light.

– Doubling or halving the f number is referred to as; stepping up; stopping down; increasing by a stop; decreasing by a stop.

Depth of field

When starting out in photography, this is often one of the first things that people want to be able to achieve because let’s face it, it looks cool.

Only one plane of the subject – the plane of sharp focus – is rendered absolutely pin-sharp.

Subjects close to this plane but not actually in it are recorded less sharply, but they do not snap suddenly out of focus. The transition from sharp to unsharp on either side of the plane of sharp focus is gradual and progressive.

In effect, subjects are in tolerably sharp focus not just in one plane, but over a range of distances – a zone of sharp focus. The depth of this zone is known as the depth of field.

Depth of field is directly proportional to aperture, and the depth of the field of focus is at its most shallow at wide apertures. Stopping the lens down to smaller apertures increases depth of field, bringing more of the subject into focus.

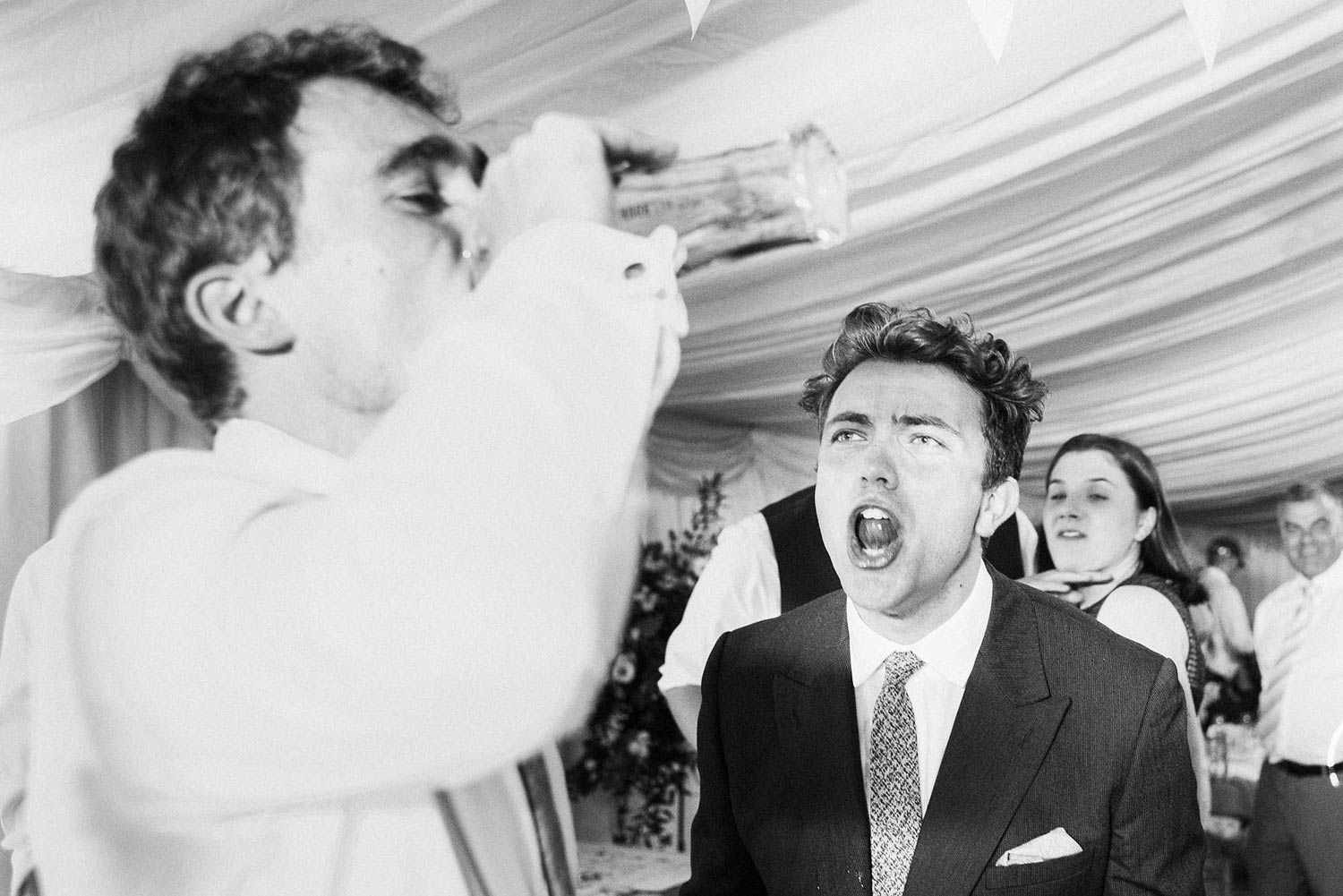

When you need the entire image to be sharp, you need to stop the lens down to a small aperture, such as f11 or 16. However, great depth of field is not always desirable, and a photographer may deliberately choose a wide aperture to reduce the depth of field – perhaps to blur an unsightly background behind a portrait subject.

Aperture is not the only factor that influences depth of field. Focal length and subject distance do too. Long focal length lenses (see lens types) have shallower depths of field, and wide-angle lenses more depth of field. This is because long lenses compress perspective and make objects appear closer together.

Shallow depth of field

Here is an example of how depth of field effects an image. A wide aperture of f/2.8 has been used. The image was manually focused so the Baby Blue Hubbard Pumpkins were sharp. Shooting with a wide aperture of f/2.8 has created a shallow depth of field, the effects of which can be seen below. There is a field of sharp focus, in front and beyond that field the image becomes increasingly out of focus.

What better way to explore aperture than with cake? This image was shot at an even wider aperture of f/1.4. The depth of field is so shallow that the flowers at the front of the cake a pin sharp and the icing and lettering at the top begins to be rendered out of focus, a distance of approximately three inches. The flowers in the background are completely out of focus. Shallow depth of field can be a wonderful tool in composition as it can render unsightly objects in the background out of focus.

Don’t forget, depth of field also works on objects in the foreground.

Takeaway:

Depth of field is how much of the image is in focus

Changing the aperture changes the depth of field

Small apertures – deep plane of focus

Large apertures – shallow plane of focus

Small apertures – good for landscape

Large apertures – good for indoors/lowlight and blurring the background

Estimating depth of field

On SLR cameras, the lens is set to full aperture until immediately before exposure, the purpose of this is to let as much light into the viewfinder as possible.

If it adjusted the light levels as you changed the aperture the viewfinder would become too dark or too bright and composing the subject would become difficult.

Cameras have what is called a depth of field preview button. It varies in location depending on the camera manufacturer, see the instructions to find yours. This will set the lens to the aperture selected to give a more accurate depiction of the final image. Personally I’ve never found this particularly useful, but what is really useful is the markings on the lens itself which allow you to calculate depth of field relative to distance.

Hyperfocal distance

You may have seen that your lens has a little infinity mark on it. When focussed to infinity, the middle ground of your photograph will be in focus, however the potential depth of field at the other end of the scale is wasted because nothing can go beyond infinity. The wasted part of the depth of field can be put to use by positioning the infinity symbol opposite the depth of field marking for the chosen aperture. The entire zone of sharp focus will then be on the near side of infinity and more of the picture will be sharp.

What is Bokeh in Photography?

First off, how do you say it?

It’s surprisingly easy when you hear a Japanese speaker say it: Bo-Keh

Not Bor-Kah, or Bouquet.

A sharp Bo, not like Bow, but like Boh.

And a sharp Keh, not like Ker, or Ka. Keh.

Bokeh in photography is this:

Bokeh is a photography technique that involves using out-of-focus areas to create an aesthetically pleasing effect in a photograph. Different colours and intensities of light will vary the outcome of your Bokeh. The most interesting effects come from inventing your own shaped filters.

Let me explain.

Bokeh comes about because of the shape of you aperture. In a camera lens, aperture blades make a circle, so the out of focus areas in the above image are rendered on the image as a circle.

But you can play with this.

Any shape you manipulate your aperture to be will result in the Bokeh being that same shape.

I’ll write a detailed post on this, but for now if you want to create your own custom Bokeh shape, simply cut some black card o fit the front of your lens, cut out the desired shape in the middle and then hold it in front of the lens when you take your pictures. Remember, you can have more than one hole, play around and see what you come up with.

Summary

what is the aperture? – it’s the hole in the lens that lets in light

What’s an f number? What’s a stop?

– The scale of f/numbers (or stops) progresses like this: f/1.4, f/2, f/2.8, f/4, f/5.6, f/8, f/11, f/16, f/22 etc.

Depth of field

Depth of field is how much of the image is in focus

Changing the aperture changes the depth of field

Small apertures – everything is in focus

large apertures – very little is in focus

Small apertures – good for landscape

large apertures – good for indoors/lowlight and blurring the background