Following on from my article looking at the first ever photograph by Joseph Nicephore Niepce, here we move on to the next incredibly significant part of photographic history, the development of the Daguerreotype.

The Daguerreotype

After the publication of the process, the daguerreotype captured the attention of the public, and was an immediate success.

This image, Intérieur d’un cabinet de curiosité (Interior of a cabinet of curiosities) was made by Daguerre in 1837 and is the oldest known Daguerrotype.

Suppliers of chemicals and apparatus were besieged by would-be photographers anxious to try it.

The instruction manual written by Daguerre ran into 29 editions before the end of 1839. As the news spread, there was the same excitement in other countries in Europe, and in America, where the first daguerreotype was made in September 1839.

But in England, enthusiasm was dampened. Five days before the process was published in France, a patent was granted to an agent acting on behalf of Daguerre which restricted its use in England by anyone other than Daguerre or his licensees.

In America the process was used on a large scale until the late 1850’s when the new negative-positive process permitted the production of many copies of each picture and the daguerreotype became obsolete.

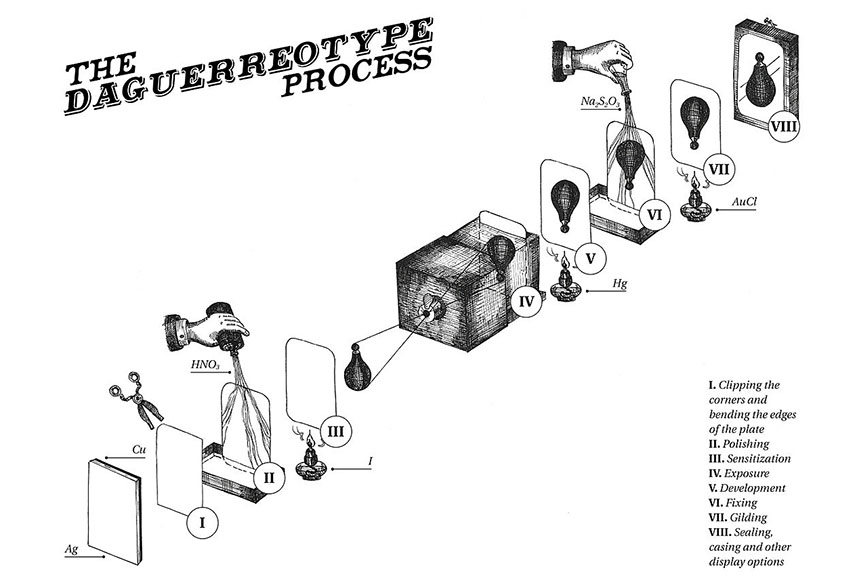

For context and to display how labour intensive the Daguerreotype process is, here is an exquisite video made by Patrick Richardson Wright of photographer Dan Carillo

The quality of the American Daguerreotypes was often extremely good, due largely to the use of the steam-driven mechanisms to polish the plates, giving a superior finish to those polished by hand, as was the European practice.

In other countries, too, photographers and inventors experimented to improve upon Daguerre’s processes and equipment. In England it was found that either Bromine vapour or Chlorine used in addition to Iodine greatly increased the sensitivity of the plate.

Lenses were vastly improved, initially by a design by Charles Chevalier with an aperture of f4.9 and then by Josef Petzval whose f3.6 portrait lens design remained in use for the next 100 years.

These improvements brought exposure times down to a matter of seconds rather than minutes and made portraiture practical even for indoor studios.

Fun fact – Petzval lenses made a comeback via a kickstarter campaign, and they’re really, really cool – https://shop.lomography.com/en/lenses

Read more about petzval lenses – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Petzval_lens

As a result, portraiture swiftly became the most popular use for daguerreotypes, although many architectural and landscape examples survive. The finished daguerreotype image was laterally reversed, as in a mirror, and was of a cold, greyish tone, showing up as a positive when the silvered plate was held so as to reflect a dark ground.

Plates could be tinted by hand, using dry powder colours fixed to the plate by breathing on it. The exposed and processed plate was covered with a protective glass, with a decorative brass matte between the frame and the picture.

It is difficult to appreciate today the impact that the introduction of the daguerreotype had on the world. To many it seemed magical that the light could draw its own picture.

While hundreds queued and paid to see displays of the new pictures, others dismissed them as blasphemes – they believed that no machine should fix the image of God’s nature.

Despite the initial excitement of the public, the Daguerreotype process was doomed to extinction almost from its birth. The negative-positive process, devised by Henry Fox Talbot and published by him soon after the first announcement of Daguerre’s process, was to evolve into modern photography.